I’ve often said that I can learn more from those who disagree with me than those who don’t.

Case in point, today’s guest post from St. Louis CyclingSavvy instructor Karen Karabell. I disagree — strongly — with the idea that it’s riskier to ride in a bike lane than in the flow of traffic, which contradicts both my own experience and most, if not all, of the studies I’ve seen.

So I invited Karen to explain her approach to bicycling, and she graciously agreed, as follows.

………

Oh, the wonders of the Internet, abolishing time and space in nanoseconds!

On this site, Ted Rogers wrote: “A St. Louis cycling instructor claims that bike lanes are dangerous with no evidence to back it up.”

With lightning speed these words made their way to me (that instructor). I was indignant. I never said that bike lanes are dangerous. I said that riding in a bike lane is more dangerous than riding in the flow of traffic. I complained to Ted that he misquoted me.

Exhibiting the generous mark of a mensch, he invited me to write a guest post to clarify. He wrote: “I personally believe riding in a bike lane is safer and more enjoyable than riding in the traffic lane, and have expressed that opinion many times. It would be good to have someone explain the other side of the debate, and you are clearly very articulate and able to do it without being argumentative—which seems like a rare quality these days.”

Thank you, Ted! Here goes…

I cannot count the number of times this image from a Los Angeles Metro Bus has crossed my Facebook feed. “Did you see this?” one friend after another asks.

The vision promoted on the back of this bus is wonderful. “Every lane is a bike lane” is a powerful statement promoting cyclist equality on our public roadways. I am all for that!

My friends know that I am no fan of bike lanes. But before explaining why, I want to make an observation about our fellow road users:

Every second on this planet,

millions of motorists are driving along

and NOT hitting what is right in front of them.

Motorists do not hit what’s in front of them because that is where they are looking. I know. This sounds like a “duh” statement. But consider the illustrations below. The green area represents a motorist’s primary “Cone of Focus”:

Courtesy of Keri Caffrey

As speeds go higher, a motorist’s “Cone of Focus” diminishes:

Courtesy of Keri Caffrey

As I’m sure is true for all of your readers, I was heartbroken when I learned of the death last December of Milton Olin Jr., the entertainment industry executive who was struck and killed by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy on routine patrol. Milton Olin was riding in a bike lane on Mulholland Highway.

We need to recognize a simple fact about bike lanes. They tend to make the people in them irrelevant to other traffic. When you are not in the way, you are irrelevant. At low speed differentials, irrelevancy might be OK. But at high speed differentials, the slightest motorist error can be devastating.

The speed limit on Mulholland Highway is 50 mph.

The last place a cyclist should be irrelevant is on a high-speed arterial road.

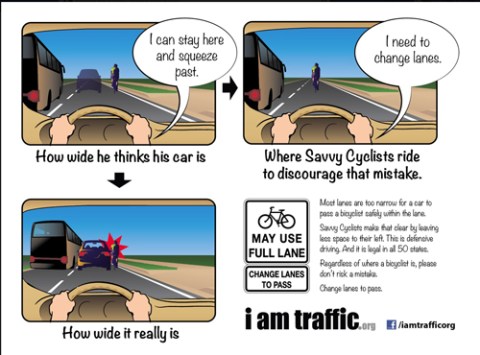

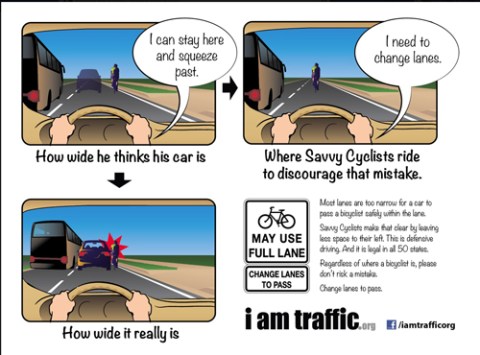

Regarding cyclist positioning on roadways, CyclingSavvy founders Keri Caffrey and Mighk Wilson made a remarkable discovery.

On roads with good sight lines—typical of most arterial roads—cyclists who control their travel lanes are seen by motorists from 1,280 feet away. Cyclists who ride on the right edge of the road—where most bike lanes are—are not seen by motorists until they are very nearly on top of them—about 140 feet away.

This is profound. We discuss this when we teach CyclingSavvy. The classroom session is incredibly engaging. Our participants soak up the information that we present. They understand exactly what we are talking about regarding traffic patterns and simple-to-learn techniques that make riding a bicycle in traffic very safe.

Most of them, however, don’t believe us—until we take them out on the road and show them.

After a classroom session last summer, a St. Louis newspaper columnist wrote: “The motorists in the training session are the rational, responsible ones. But what about the others—the ones who are speeding, talking on their cell phones and eating French fries, all at the same time?”

I loved that! In every session since, I have brought up his observation. I tell our students: “I would rather give those motorists the opportunity to see me from a quarter-mile away, rather than 140 feet!”

Being “in the way” works. Even the multi-tasking French fry eaters change lanes to pass.

Last fall one of my favorite arterial roads was put on a “road diet” and striped with bike lanes. Manchester Road in the City of St. Louis used to have two regular travel lanes in each direction. It was easy to ride on. As I controlled the right lane, motorists used the left lane to pass.

Unless motorists are making a right turn, they don’t like to be behind cyclists. Yet I rarely experienced incivility on Manchester, because motorists could see me from many blocks away, and changed lanes well before they got anywhere close to me.

Now, when riding in the new bike lane, many motorists are so close that I could reach out my left arm and touch their cars as they pass. The bike lane places cyclists much closer to motorists than do regular travel lanes.

It is my understanding that in southern California, there are bike lanes that are eight feet wide. I have been told that these wide bike lanes are well marked, so that motorists merge into them well before reaching intersections to make right turns. That sounds lovely! I can envision bike lanes such as these being useful, especially on arterial roads with few intersections or driveways.

But this is not what we have in St. Louis.

The “new” Manchester Road in St. Louis (October 2013)

Does this bike lane look encouraging? People who are afraid to ride in traffic don’t want to ride here, either.

Riding in a bike lane requires more cycling skill than riding in travel lanes. That’s why CyclingSavvy can teach novices to ride in regular traffic lanes, even on arterial roads. It’s easier and safer.

No discussion about bike lanes would be complete without reference to “right hooks” and “left crosses”—new phrases in our lexicon, thanks to bike lanes.

The last time I rode in the bike lane on Manchester Road, I was in the way of three right-turning motorists:

- The first apparently did not see me. She would have right-hooked me, had I not slowed down to let her turn in front of me.

- The second motorist saw me and stopped in the now-single travel lane, holding up a line of motorists behind him as he waited for me to get through the intersection. I stopped, too, because I wasn’t sure what he was going to do. He smiled kindly. We shook our heads at each other as he waved me on. I proceeded with caution.

- I can’t remember the circumstances in which the bike lane put me in the way of the THIRD right-turning motorist. By this time I was disgusted, and emotionally spent. It is exhausting to be on the lookout at every single intersection and driveway when using a bike lane on an urban arterial roadway.

Travel was never this difficult on the “old” Manchester Road.

As cyclists, being in a bike lane increases our workload. We ideally need eyes in the back of our heads to constantly monitor what is happening behind us. I use an excellent helmet-mounted rear view mirror. I would not dare ride in a bike lane without one.

When I am controlling a regular travel lane, I find that I never need to exercise white-knuckle vigilance. Mindfulness, yes. Unfortunately there are a relatively small number of psychopaths and other unsavory types piloting land missiles on our roadways. It may seem counterintuitive, but lane control actually gives cyclists more space and time to deal with these rare encounters.

In a bike lane I have learned to ride at no more than half my normal speed to compensate for potential motorist error. My normal speed isn’t that fast—about 12 to 18 mph, depending on conditions.

This self-enforced slowdown for safety is irritating. I have somewhere to go, too! What makes people think the time of a motorist is more valuable than that of a cyclist?

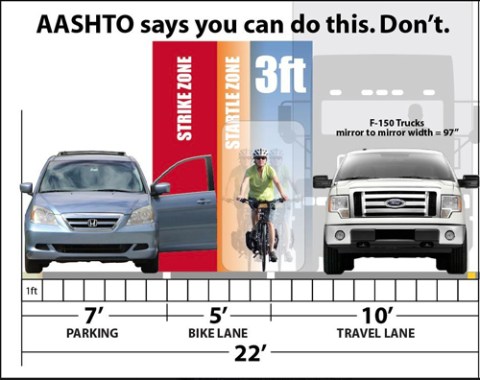

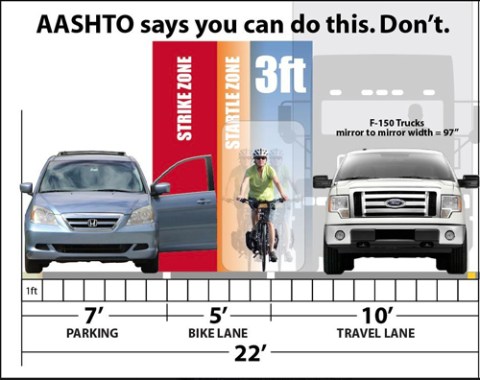

We cannot ignore the danger of getting “doored,” another terrible feature of many urban bike lanes. Keri Caffrey has done a brilliant job illustrating the reality of space in a typical bike lane:

Traffic engineers would not dream of manufacturing conflict between two lanes of motor vehicle traffic by placing a right-turn lane to the left of a through lane. Why is this acceptable when one of the lanes is for bicyclists?

An engineer friend who is painfully aware of the quandary presented by bike lane design argues that municipalities have a responsibility to warn users of their unintended risks, much as the pharmaceutical industry already does regarding the potential side effects of their products.

On the bright side, my husband has taught me a great technique. We use bike lanes as “Control & Release” lanes.

“Control & Release” is a CyclingSavvy technique. We teach cyclists how to use lane control as their default position in managing their space on the road. But we also teach them how to determine when it is safe to move right and “release” faster-moving traffic.

How does this work with bike lanes? Because of traffic signalization, motorists tend to travel in platoons. Even the busiest roads have expanses of empty roadway, while motorists sit and wait at traffic lights.

When we are on roads with bike lanes, being aware of the “platoon effect” allows us to use the regular travel lane and ride happily along at our normal speeds. We typically cover a city block or two without having any motor traffic behind us. When a platoon approaches, we move over to the bike lane and go slow, very slow if it’s a door-zone bike lane. It takes only a few seconds for the platoon to pass.

Once they pass, we move back into the travel lane and rock on.

Harold Karabell using the regular travel lane in Buffalo, NY, but moving over to the door-zone bike lane as necessary to release motor traffic behind him (July 2013)

Because bicycling is very safe, accidents are rare, even in bike lanes. But the next time you hear about a motorist hitting a cyclist, pay attention to the details. Where was the cyclist on the roadway? Was the cyclist on the right edge of the road? If he or she wasn’t breaking the law—for example, by riding against traffic, disobeying signals or riding at night without lights—very likely the cyclist was riding near the right edge, where bike lanes are.

We who care about bicycling want more people to choose bicycling, especially for transportation. Half of all U.S. motor trips are less than three miles in distance. This is very easy to traverse by bicycle—usually just as fast and sometimes faster than using a car. Can you imagine the transportation revolution if Americans left their motor vehicles at home and used their bicycles instead for short trips? I for one would feel like I was living in paradise!

But how do we get there? Professor Andy Cline argues that we are making a grave mistake in our attempts to channelize and “segregate” cyclists from motorists. Indeed, as we are reframing U.S. roadways to accommodate bicycling, he warns that we must avoid “surrendering our streets.” This is what we are doing when we ask for cycletracks or special paint markings on the edge of the road.

If we keep asking, we are eventually forced into the bars of our own prison. California is one of eight states that require cyclists to use bike lanes when the lanes are provided.

If we would connect the dots and learn just one thing from the hundreds of bike lane deaths over the last 20 years, it would be this: Attempting to segregate by vehicle type does not work. It just makes transportation more difficult for both cyclists and motorists.

Make no mistake: Bicycles are vehicles. Most states define them as such. Some states define the bicycle as a “device.” But in all 50 states, cyclists are considered drivers.

What excites me is the vision put forth by the American Bicycling Education Association. We believe that people will choose bicycling when they feel expected and respected as a normal part of traffic.

We recognize that we are outliers. We are not waiting for a future in which we hope to receive the respect of the culture. We respect ourselves now. We exercise that self-respect by participating in regular traffic, like any other driver.

Our experience has convinced us that cycling as a regular part of traffic works beautifully.

In a Utopian world this is well and good, a friend likes to say. But what if everybody starts using bicycles in traffic? How will motorists react then?

Our desire for on-road equality has been compared by some to the struggles fought by African Americans, gay people or other maligned minorities seeking acceptance and equality. On only one point does this “civil rights” comparison resonate for me: The prejudicial assertion that cyclists cause delay to other drivers.

Cyclists causing delay is a myth that must die. This pernicious stereotype oppresses us. It simply is not true. As cyclists traveling solo, with one other person or even in a small group, we are incapable of causing significant delay to other road users.

The truth about on-road delay is just the opposite. Last December Harold and I were in Dallas. As our friends Eliot Landrum and Waco Moore escorted us to dinner, we were caught in one of that city’s routine traffic jams:

Evening rush hour on Oak Lawn Avenue in Dallas (December 2013)

Lest anyone think that we cyclists were causing delay, I put the kickstand down on my bicycle and walked behind Waco, Harold and Eliot to take a forward-facing photo:

Forward view of rush hour on Oak Lawn Avenue

City lights and welcome company made this evening lovely. Otherwise, this was just another routine ride for cyclists who practice driver behavior.

Motorists delay motorists. The sheer number of motorists is what causes the most delay on our roads. Many things cause momentary delay, such as traffic signals, railroad crossings, and vehicles that make routine stops, like delivery trucks–and city buses.

In a snarky moment I remember responding to one Facebook friend: “Thank God every travel lane is not a bike lane!”

Yet this marketing campaign from the City of Angels made my heart soar.

It will be a great day when every cyclist can—without fear or risk of harassment—use any traffic lane that best serves his or her destination.

I envision our existing roadways filled with people using the vehicles that best serve that day’s transportation needs. More often than not, these vehicles will be bicycles—because who needs a two-ton land missile to go to work, or buy a loaf of bread? I envision the people of Amsterdam and Copenhagen flocking to the United States to ask how we did it. How did we get cyclists and motorists to integrate so peacefully and easily on our roads?

We have discovered that when cyclists act as drivers, and when all drivers follow the rules of the road, traffic flows beautifully. This is simple. This is safe. This offers a sustainable and inviting future.

But don’t take my word for it. Come ride with me!

……….

Karen Karabell is a mother, business owner and CyclingSavvy instructor in St. Louis who uses her bicycle year-round for transportation. She is passionate about helping others transform themselves, as she did, from fear of motor vehicle traffic to mastery and enjoyment.

Karen Karabell is a mother, business owner and CyclingSavvy instructor in St. Louis who uses her bicycle year-round for transportation. She is passionate about helping others transform themselves, as she did, from fear of motor vehicle traffic to mastery and enjoyment.

Like this:

Like Loading...